Heartworm in Dogs

Heartworm in Dogs

By Meg Hamill

Bachelor of Biomedical Science student

Deakin University

Heartworm disease in dogs is caused by the parasitic nematode Dirofilaria immitis and is transmitted by mosquitos. Heartworm is endemic in southeast Australia, but the risk of developing heartworm disease is rare, and the prevalence of disease is low (1). The symptoms of disease vary depending on how many worms are present, how long the dog has been infected with heartworm for and the degree of damage to organs such as the lungs, kidneys, liver and of course the heart. Signs and symptoms can include coughing, tiredness after moderate exercise, breathing troubles, decreased appetite, weight loss, and in some extreme cases sudden blockages of blood flow in the heart, which is life-threatening (2). The best treatment for heartworm disease is prevention, and with many treatment options available, there is sure to be one to suit everyone’s and every dog’s lifestyle.

The Heartworm lifecycle

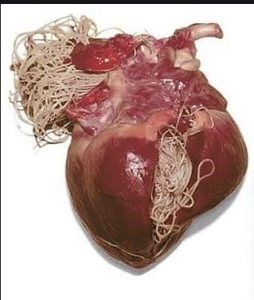

Heartworms are parasites that are able to live inside the arteries of the lung and chambers of a pet's heart and feed on the continuous supply of blood available to them. In severe cases, heartworms can grow up to 30cm long and 2cm thick in populations of over 200. The offspring of a heartworm are more commonly referred to as microfilariae, which can be found in the blood of an infected dog (3).

|

|

|

Microfilaria found in the blood viewed under a microscope (x400). Microfilariae are 250 to 300 μm (.25 to .3 mm) in length, compared to the dog’s red blood cells which have a diameter of 6 to 8 μm (.006 to .008 mm) (4)(5). Video courtesy of Okstate Parasit D-lab (6). |

Mature heartworms develop inside the heart and major blood vessels where they interrupt blood. They tend to accumulate on the right side of the heart as shown in the image (in pictures of the heart, the right side is actually shown to be on the left, and the left is shown to be on the right). Image courtesy of Vet4Bulldog (7). |

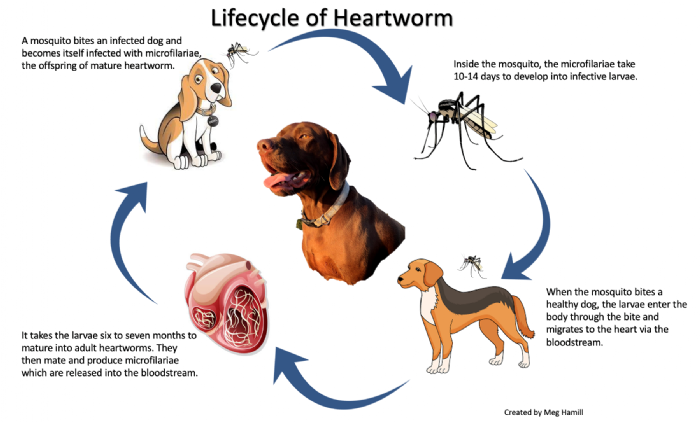

For dogs to become infected with heartworms, a mosquito is needed and acts as an intermediate host. The lifecycle begins when a mosquito bites an infected dog and the mosquito itself becomes infected with microfilariae. Over the course of 10-14 days, these microfilariae develop inside the mosquito’s gut resulting in infective larvae which then travel through the mosquito to its mouth. When the mosquito bites another dog, the larvae spread to the dog through the bite site, where they migrate into the bloodstream and move to the heart and nearby blood vessels. It takes around six to seven months for the larvae to mature into adult heartworms, which can then mate and produce microfilariae offspring. The microfilariae are then released into the bloodstream, and the cycle is complete. This is shown in the diagram below (3,8)

How do heartworms affect dogs?

It can take years of infestation with heartworms before clinical signs begin to show. When heartworms mature, they begin to clog the heart along with the major blood vessels. Due to these obstructions, blood cannot flow freely and the blood supply to major organs is diminished. Without enough blood, and therefore oxygen, organs such as the kidneys, liver and lungs all begin to malfunction and are unable to perform their necessary roles (8).

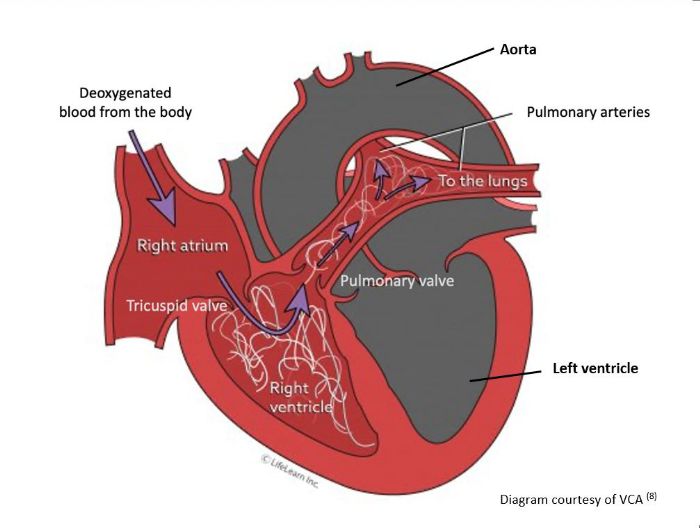

Adult heartworms are very slow moving and are unable to attach to the walls of blood vessels or the heart, or swim, so their movement is essentially dictated by blood flow. When deoxygenated blood comes back to the heart, it travels through the right atrium and then the right ventricle, before being pushed through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs to become oxygenated.

Due to this flow of blood, the heartworms tend to accumulate in the pulmonary arteries.

In extreme cases, the heart is unable to push blood through the arteries with the normal force, which means heartworms are able to migrate back to the right atrium and ventricle and then accumulate. The tricuspid valve is located between these two chambers and prevents blood flowing from the ventricle back to the atrium when the heart contracts (beats). With the accumulation of heartworms however, the valve cannot close correctly, leading to regurgitation of blood back into the atrium, and incorrect filling of the ventricle. Another valve affected is the pulmonary valve which is located between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. In a healthy dog, this valve opens during contraction to allow blood to be pushed from the right ventricle to the pulmonary arteries and closes to prevent the flow of blood back into the ventricle. With the accumulation of heartworms, the pulmonary valve cannot open properly, so less blood is pumped to the lungs for oxygenation. It also cannot close properly during relaxation, so blood from the arteries can flow back into the ventricle. Both these things can lead to sudden cardiac collapse and unfortunately sudden death (9).

Microfilariae can also have an effect on the dog’s general health. As microfilariae circulate through the body, they mostly stay in the smallest blood vessels called capillaries where they are can become lodged and block blood flow. The tissues mainly effected by microfilaria are the lungs and liver as both of these organs are the major sites of oxygen and nutrient exchange, so contain the greatest number of capillaries. Without oxygen, these organs begin to deteriorate (8).

How is a dog tested and treated for heartworms and how is heartworm disease prevented?

To test for heartworms in canines, a veterinarian is able to use two kinds of blood tests. One tests for mature heartworms present and the other for the presence of microfilariae. Both are accurate, but only effective after 6 months of infection due to the length of time it takes for the larvae to mature into adult heartworms and then reproduce. If heartworms are found there is treatment available. The dog can be treated with an injection of melarsomine which will kill the adult heartworms. They can also then be treated with a topical solution of imidacloprid and moxidectin which will eliminate the microfilaria. Both are expensive and may be toxic to some dogs (3).

The best treatment therefore is prevention.

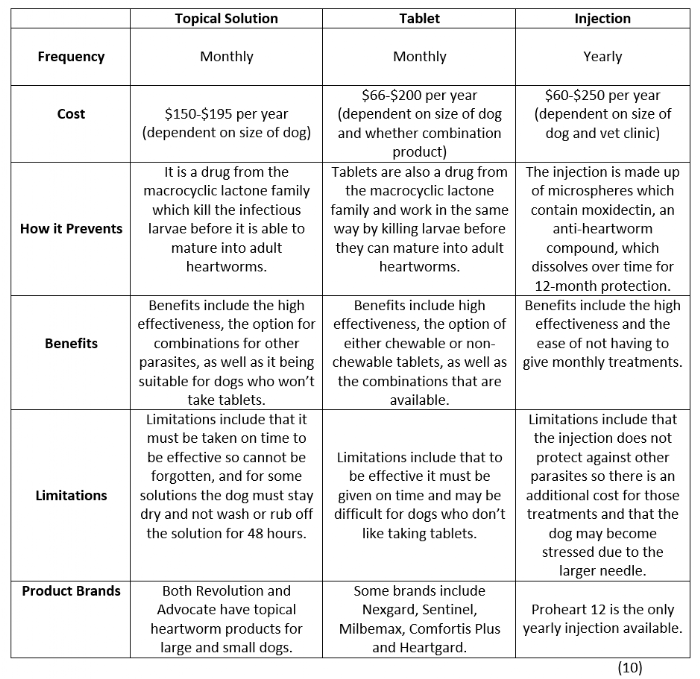

There are many different Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved products that can prevent heartworm, including daily, monthly and yearly treatments. Tablets, both chewable and non- chewable, topical liquids or an injection are all viable options. Some treatments also contain other ingredients which are effective against other parasites like flea’s, ticks, as well as other worms like roundworms and hookworms (3). Prevention methods against heartworm can begin as early as six to eight weeks. If preventative measures begin after 7 months of age, dogs should be tested for heartworm first to make sure they are not already infected. The table below shows how some of the more popular methods work, as well as similarities and differences between them.

This table includes general information so before using any treatments consult your veterinarian.

There has been recent evidence in the U.S that suggests some Dirofilaria immitis (Heartworm) have become resistant to macrocyclic lactone, the primary drug used to prevent heartworm disease. A project funded by the Canine Research Foundation led by Professor Jan Šlapeta (University of Sydney) aimed to examine whether this resistance is also seen in Australian cases. Researchers were able to sequence the whole genome of Dirofilaria immitis found in Australia, which can now be compared to the sequence found in the mutated heartworm in the U.S to see if there are similarities (11). See here for more information: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpvbd.2021.100007

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Emeritus Prof Brian Corbitt and Dr Steven Holloway (BVSc MVS PhD MACVSc Dipl. ACVIM) for valuable comments on the article.

References

- Nguyen C, Koh W L, Casteriano A, Beijerink N, Godfrey C, Brown G, Emery D, Šlapeta J. Mosquito-borne heartworm Dirofilaria immitis in dogs from Australia. Parasites Vectors [internet]. 2016 Oct 7 [cited 2021 Sept 1]; 9(535): 11pp. Available from doi: 10.1186/s13071-016-1821-x

- American Heartworm Society [internet]. North Carolina: American Heartworm Society; c2021. Heartworm in Dogs. N.d. [cited 2021 Sept 1]; [about 5 pages]. Available at: https://www.heartwormsociety.org/heartworms-in-dogs#is-there-a-vaccine-for-heartworm-disease

- U.S Food and Drug Administration [internet]. USA: FDA; c2021. Keep the Worms Out of Your Pet’s Heart! The Facts about Heartworm Disease. 2019 Aug 22 [cited 2021 Sept 2]; [about 9 pages]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/animal-veterinary/animal-health-literacy/keep-worms-out-your-pets-heart-facts-about-heartworm-disease

- Cross J. Filarial Nematodes. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology [internet]. 4th ed. Galveston, Texas: University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. [cited 2021 Sept 6]; chap. 92. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7844/

- Adili N, Melizi M, Belabbas H. Species determination using the rd blood cells morphometry in domestic animals. Vet. World [internet]. 2016 Sept [cited 2021 Sept 16]; 9(9): pp.960-963. Available from doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2016.960-963

- Okstate Parasit D-lab. Dirofilaria immitis – microfilaria [video on internet]. Oklahoma: Oklahoma State University Centre for Veterinary Health Sciences;2012 Dec 29; [cited 2021 Sept 16]. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I60LmDO6Xiw

- Vet4Bulldog [internet]. California: Vet4Bulldog; c2018. Heartworm disease in bulldogs and French bulldogs. N.d. [cited 2021 Sept 16]; [about 5 pages]. Available from: https://vet4bulldog.com/heartworm-disease-in-bulldog-and-french-bulldogs/

- Barnette C, Ward E. VCA [internet]. California: VCA Hospitals; c2021. Heartworm Disease in Dogs. N.d. [cited 2021 Sept 2]; [about 7 pages]. Available from: https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/heartworm-disease-in-dogs

- Jones S L. TVA [Internet]. Today’s Veterinary Practice; c2021. Canine Caval Syndrome Series, Part 1: Understanding Development of Caval Syndrome. N.d. [cited 2021 Sept 15]; [about 9 pages]. Available from: https://todaysveterinarypractice.com/ahs-heartworm-hotlinepart-1-understanding-development-caval-syndrome/

- Paszkowski C. Pet Circle [internet]. Pet Circle; c2021. What is the best heartworm treatment for dogs? 2020 Jan 6 [cited 2021 Sept 5]; [about 7 pages]. Available from: https://www.petcircle.com.au/discover/what-is-the-best-heartworm-treatment

- Ching-Wai Lau D, McLeod S, Collaery S, Peou S, Truc Tran A, Liang M, Šlapeta J. Whole-genome reference of Dirofilaria immitis from Australia to determine single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with macrocyclic lactone resistance in the USA. CRPVBD [internet]. 2021 [cited 15 Sept 2021]; 1(100007): 5pp. Available from doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpvbd.2021.100007